Justin Bright’s Wild Life: Skateboarding 1,000 Miles Across Florida

We’re kicking off our Wild Floridians series with Justin Bright, who skateboarded more than 1,000 miles across Florida raising awareness about its wild places.

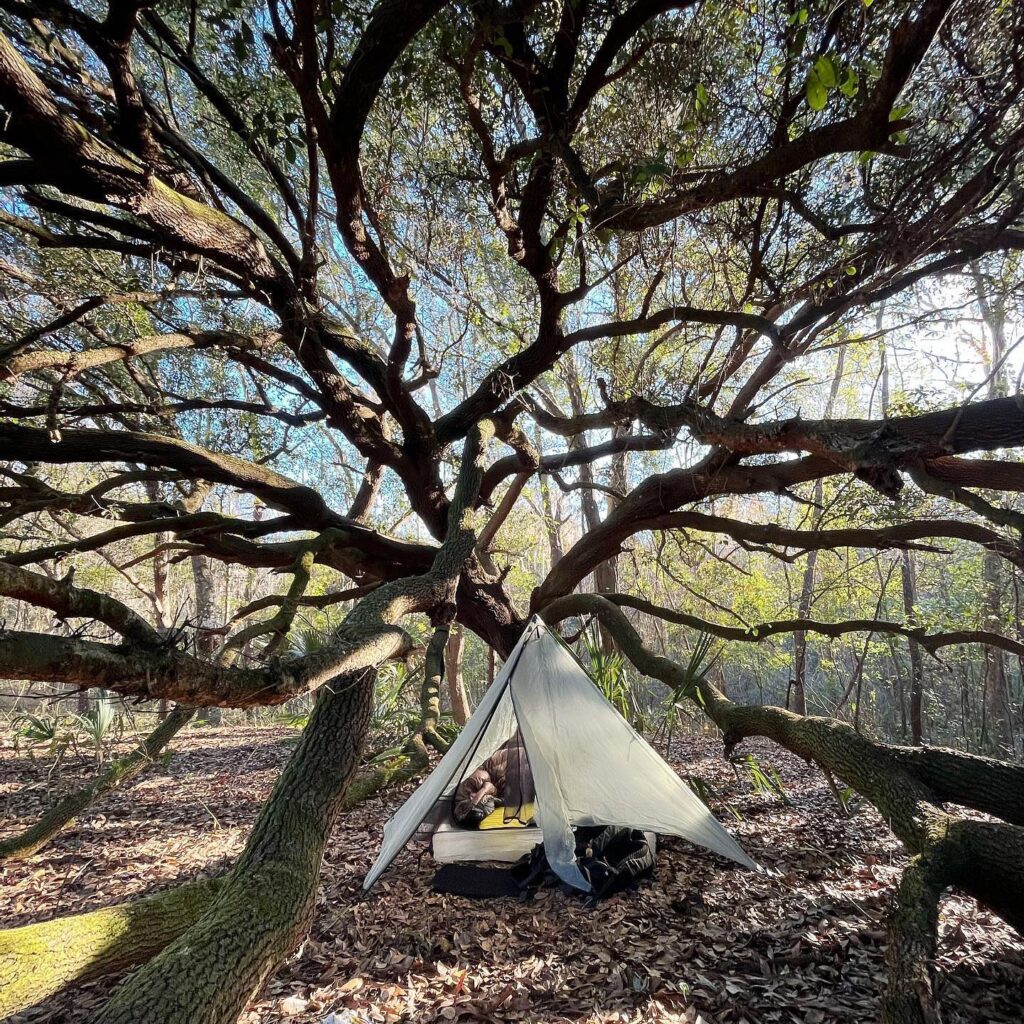

Riding a longboard, living off Ramen noodles and camping with wild boars is not how most of us imagine traveling across Florida. But that’s how Justin Bright spent his once-in-a-lifetime journey carving the Corridor last January with only a backpack, helmet and camera in tow.

Skating more than 1,000 miles from the Panhandle to the Florida Keys, Bright took photos and videos to document his travels and raised almost $11,000 for Conservation Florida.

Live Wildly Impact Partner Callout: Conservation Florida is a statewide land conservancy non-profit dedicated to protecting Florida’s lands and the Florida Wildlife Corridor.

From observing the lush Ocala National Forest and the Everglades to sharing meals with kind strangers who later became friends, Bright experienced Florida in a way that most people never knew possible.

He shared with us the importance of slowing down, what he wishes people knew about Florida and how he embraces the Live Wildly spirit in his daily life.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Live Wildly: What was it like growing up in Florida?

Justin Bright: I’m from St. Petersburg. In St. Pete, you’re surrounded by water and there’s no way out. My dad grew up fishing and running around the beaches, and my brother and I did the same.

At an early age, I could tell there’s a disconnect between the wild places in Florida and the land where people inhabit.

At an early age, I could tell there’s a disconnect between the wild places in Florida and the land where people inhabit. This is the third-largest state in the country and there’s still so much green space and wild places here, but what’s left is being rapidly developed. It’s a challenge for someone who grows up here and sees me living here in the future.

LW: Most people wouldn’t think to skateboard more than 1,000 miles. How did this idea come about?

JB: It was one of those things that was spoken into existence over time. I had said it so many times that I wanted to hold myself accountable. I pulled the trigger and decided to do the whole thing because as far as I knew, nobody had actually skateboarded from Pensacola to Key West, and that was intriguing to me.

Florida is my home state and means so much to me. I viewed this as a way to travel the state, because it’s a really intimate way to travel by going very slowly, compared to going by car. You just come as you are.

Florida is my home state and means so much to me. I viewed this as a way to travel the state, because it’s a really intimate way to travel by going very slowly, compared to going by car. You just come as you are.

LW: I know you had a personal goal, but it seems there was a larger pull for you to do a trip like this. What was it?

JB: If nothing else, I wanted people to see the state. I feel like people who live in Orlando, Tampa or Miami are very close to so many precious places, but they’ve never seen them. Some Floridians say they’ve never seen an alligator — that’s crazy because they’re everywhere!

There’s so much that’s being taken away that people say they don’t even recognize Florida. I wanted people to get their eyes on the real Florida, because it really is like its own country. There’s so many varieties of people, cultures and landscapes — it’s unlike anything else in the world.

LW: How did you plan your route?

JB: There was no choice for me but to ride on the roads that have carved up this whole state.

That’s the central part of the issue surrounding the Florida Wildlife Corridor — having a connected landscape where animals and plants can disperse across the state freely and not have to worry about habitat fragmentation.

That’s the central part of the issue surrounding the Florida Wildlife Corridor — having a connected landscape where animals and plants can disperse across the state freely and not have to worry about habitat fragmentation.

I didn’t necessarily take the fastest way. I definitely routed through some ecologically significant and sensitive areas intentionally so that I could take photos and video showing people the crown jewels of Florida. Some of it was difficult and I didn’t always have lots of resources, but that was the point — to make it challenging. We have already made it so convenient to cross the state for humans, and it’s very inconvenient for a lot of other critters that try to make their way.

LW: You partnered with Conservation Florida for this trip, how did that happen?

JB: For the past three years, I was covering environmental issues in Florida and could see the blatant onslaught that we have against our natural resources and wild places. I thought it would be an interesting way to bring attention to the issue because there’s only so much figuratively shaking people by their arms and trying to yell sense into them that you can do before they listen.

I cold-called Conservation Florida two weeks before I started and told them I’m going to create a GoFund Me page for them.

When they realized I was just bumming it across the whole state without any sponsors, they wanted to make their own campaign, be my partner and support me. I don’t think we would have raised as much money if they weren’t fully supportive of it.

When they realized I was just bumming it across the whole state without any sponsors, they wanted to make their own campaign, be my partner and support me. I don’t think we would have raised as much money if they weren’t fully supportive of it.

By the end, we raised around $11,000, which, obviously, they get donations of far more than that, but to me $11,000 is a lot of money.

LW: What did you hear and see?

JB: There was so much variety from place to place, county to county. You leave the coast for five miles, and you enter a completely different habitat. It shows there are a lot of plants and wildflowers that have very, very narrow ranges — only 10 miles in Apalachicola National Forest or things of that nature. When you have endemic species that have such a narrow range, it just shows the biodiversity in the state.

One thing that kept me going throughout the trip and distracted me from traffic, gas and smells is that I’d look on the roadways for birds or listen to what I could hear by ear.

I saw or heard almost 140 different bird species during the five and a half weeks. It was cool to see a little sandpiper wintering down here, in the middle of their giant journey. I was kind of doing the same thing.

I saw or heard almost 140 different bird species during the five and a half weeks. It was cool to see a little sandpiper wintering down here, in the middle of their giant journey. I was kind of doing the same thing.

LW: What do you want people to know about the Florida Wildlife Corridor?

JB: That it exists [laughs]. The Corridor is not a mystical, perfect paradise where there’s no humans. It will inevitably include urban and suburban areas, or places that are adjacent to cities.

We are not separate from this issue. It’s not, “We live here and we’ll make a little corridor for the wildlife.” No, we have to be a part of the process.

We are not separate from this issue. It’s not, “We live here and we’ll make a little corridor for the wildlife.” No, we have to be a part of the process. That’s something that I hope people learn because, in general, there’s a disconnect between the land that we live on and our human communities.

It’s important that people see that the wilderness is an inseparable part of us.

LW: How do you ‘Live Wildly’ in your daily life?

JB: I live in Gainesville, a city with 200,000 people, and I’m from the most densely populated county in the state. I can’t pretend I live in a hut in the wilderness.

It’s important to constantly kindle a connection with the wilderness because at the end of a backpacking trip or hike, it’s so easy to come back to your house and immediately forget that was five or 20 miles from you. I make it a point to remind myself about that all the time and immerse myself in that because it is a shared space.

It’s important to constantly kindle a connection with the wilderness because at the end of a backpacking trip or hike, it’s so easy to come back to your house and immediately forget that was five or 20 miles from you. I make it a point to remind myself about that all the time and immerse myself in that because it is a shared space.

Even with photography, some people want to portray the wilderness as a pristine paradise. But it’s more helpful to show the uglier side of where animals are living. Most animals will be touched to some degree by human influence. It’s important not to photoshop out the plastic bag or giant smokestack in the background, but to include it. A lot of the times, you can read a news article and become angry because it’s your home, but then actually seeing it is much more impactful.

That was a very verbose way of saying to go outside more.

To see more pictures and videos from Justin’s journey, check out his Instagram.

“Wild Floridians” is a monthly original series that highlights Floridians across the state who embody the Live Wildly spirit and support conservation in unique ways. Do you know a Wild Floridian? Submit them for our consideration here!

Conservation Florida works with Live Wildly as a land protection partner. Interested in protecting nature and the world around you? Reach out to us at info@livewildly.com and we’ll connect you with the right team to learn more about your conservation goals.