Bikepacking in wild Florida

The Corridor’s green spaces inspired Karlos Bernart to create off-road bike paths. Now, he’s established routes spanning thousands of miles to get people closer to Florida’s wild side than ever before.

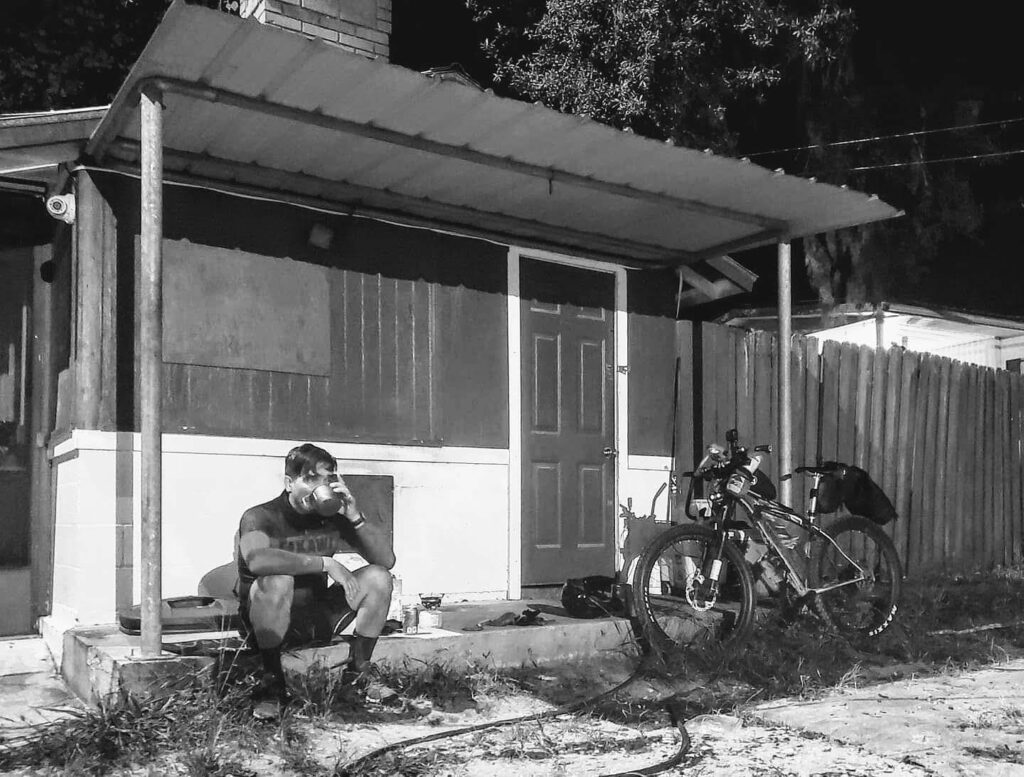

Karlos Bernart is always looking for his next big adventure. As an avid bikepacker — a combination of off-road cycling and backpacking — his outings include everything from riding a little too close to alligators in Big Cypress to pedaling through woods lit by thousands of fireflies in the Ocala National Forest.

Karlos grew up in Deltona, Fla., exploring the scrub pine woods and skateboarding everywhere he could. As an adult, he traded his skateboard in for two wheels — a bike. Today, he spends his time maintaining trails and hosting events through Single Track Samurai — a company he created that provides routes, group events and races for the cycling community in Florida.

Just as the Corridor connects green spaces across Florida for animals to travel, Karlos does the same for bikepackers. He maintains thousands of trails and hosts one of the biggest bikepacking events in the state. Sharing the routes allows Karlos to help others Live Wildly and experience the beauty and magic that come from traveling by bike.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Live Wildly: How did you get into cycling?

Karlos Bernart: From an early age, I was always into exploring. I literally spent my youth scouring through the scrub pine woods. When I was 9 years old, I saw the movie “Back to the Future” and got very into skateboarding. I used to not have a bike, so that’s how I got around.

I started cycling about 23 years ago. I started riding bikes to lose some weight and I fell in love. Someone took me to Rock Springs Run and that was the first place I ever rode bikes. It’s not the best bike trail in the world, but what made me fall in love with cycling in the woods was that it made me feel like I wasn’t in Florida. It showed me a side of Florida that I didn’t know existed. I wanted to see more, and I literally became addicted to it. It’s a type of activity where the journey is the destination.

What made me fall in love with cycling in the woods was that it made me feel like I wasn’t in Florida. It showed me a side of Florida that I didn’t know existed. I wanted to see more, and I literally became addicted to it. It’s a type of activity where the journey is the destination.

I began checking out more trails. Then, I started racing cross country mountain bikes all over the state. Once I got good at that, I did 6- and 12-hour mountain bike races. I always wanted to do the “next thing.”

LW: How did cycling lead you to create Single Track Samurai?

KB: Single Track Samurai was a nickname I acquired from racing bikes. About 15 years ago, my friend was reading an article about a gentleman who rode his bike from Canada to Mexico on the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route. It’s nearly impossible, which made me want to do it even more. To practice, I started making my own routes in Florida, my first being a 60-mile loop. Eventually, I invited people to come ride it, and sure enough, a bunch of people came. I made a longer loop and discovered that I had a knack for looking at new and old maps and satellite images to find old roads or trails that people weren’t using anymore and seeing where the green spaces were and connecting the dots.

I started making a huge, gigantic loop called the Huracan 300, which is now my biggest event and probably the third-biggest bikepacking event in the United States. Then I made coast-to-coast routes, a north-to-south route, and eventually, a Panhandle route and connected those together. I recently partnered with some folks to make a route that goes all the way to Canada.

I remember the possibility of doing a north-to-south route was inspired by that first documentary I saw about the Florida Wildlife Corridor. I thought, if they have the Florida Wildlife Corridor, they must have fire roads or service roads to protect it in case of a fire.

I remember the possibility of doing a north-to-south route was inspired by that first documentary I saw about the Florida Wildlife Corridor. I thought, if they have the Florida Wildlife Corridor, they must have fire roads or service roads to protect it in case of a fire.

Most of that is public land, so they probably have maps, too. The map of the Florida Wildlife Corridor was the first map I saw that inspired and pushed me to help create a long-distance route that goes all the way from Alabama to the Keys.

LW: Why do you think it’s so important to connect these green spaces?

KB: First, I think Floridians who do not have the opportunity to get outdoors don’t realize how awesome Florida is and the amount of good, old-fashioned dirt that is still available to use. There are some places where they don’t have green spaces. It’s such a valuable resource to us. It needs to be highlighted and shared. In the beginning, what drove me to connect these places was to share it.

In the beginning, what drove me to connect these places was to share it.

It’s also magical. You can have a transforming experience by exploring these green spaces. My initial draw and love was the fact that I felt like I was in another country, but really I was just right here in Florida. Especially when I get south of Devil’s Garden and go through Big Cypress, I feel transported. Florida is the only state that’s in the tropics. It has over 269 endemic species. We have rapids, caves, waterfalls, rocky bluffs and coral beaches. We have snakes and big cats and bears. I mean, we have it all. There are not many states in the U.S. or places outside of the U.S. that have all of that at the same time.

LW: What does the Corridor mean to you?

KB: Aside from it being a huge inspiration for me to know that it was possible to make a mostly off-road route from the top to the bottom of the state, and that it helps provide animals a safe passage and the ability to roam, it’s also such a valuable resource for us as people to escape from normal, everyday life. It gives us a chance to commune with nature—to go camping, hike three miles and feel like you’re 100 miles away from anything. It’s a valuable resource that you can’t get back. We have to protect it, because what would we do without it? Once it’s gone, it’s gone.

We have to protect it, because what would we do without it? Once it’s gone, it’s gone.

I wish that the average person would understand the value of it instead of being obsessed with more population density or more paved roads. I wish people were more aware of how important those spaces are.

LW: Let’s get back to bikepacking. Can you describe what you hear and see on your trips?

KB: It is so different depending on where I am. If I’m riding in the north near the Santa Fe River Corridor, the terrain is hillier, and the roads are harder limestone. There are big, gigantic oaks. If I’m riding through the big scrub Ocala National Forest, then there are huge views you can see for miles—big rolling hills. But the sand is different—it’s not hard packed. Now you have some sort of clay, sand mixture and pine scrub everywhere. I see scrub jays and bear tracks. I’ve been fortunate to see tons of bears.

Then, when I’m riding through Fakahatchee, I haven’t seen the ghost orchid, but I can smell it—the sweetness. Sometimes, when I’m traveling through these narrow, tropical and dense forest areas, it smells like cologne and other times it smells like the sweetest perfume. The ground acts like it doesn’t want you there and wants to push you out—not because it’s not clear for a path, but because it’s jagged, rocky and tough. I don’t know how else to describe it.

If I’m near Lake Okeechobee or the Everglades—it’s vast and wide open. I can see for miles. The trees look huge on the horizon—it’s amazing. There are not many places in Florida where you can get views that big. Finally, when you’re in the Keys, it’s like you’re in another country. The aqua blue waters, the Key deer—they’re very cute and little.

LW: Are there any moments from your cycling adventures that stick out to you?

KB: There are so many. When I first rode the trip from the Ocala National Forest through Hopkins Prairie, I hit it when the fireflies were popping, and the woods were covered with thousands of them. I’ve never in my life seen that many fireflies in one place—it was just incredible. I would have never seen that if I hadn’t been on my bike at that moment. That’s the beauty of traveling by bike. You have tons of experiences like that.

Another part that sticks out in my mind was when I was riding through the Everglades and Big Cypress. I learned that you can’t ride too close to the edge of the road because the gators like to hang out right there and numerous times, they scared the crap out of me. Most of the time they scurry away from you, but it scares me every time, even today.

LW: How do you ‘Live Wildly’ on and off the bicycle?

KB: I try to stay out of my car as much as possible. I have a bicycle that I use to go food shopping and take my kid to school. I also have boats that pack to the size of a paper towel that we blow up to float on rivers, and they’re strong enough to put my bike on them.

I love how every summer, as if by clockwork, we visit the bioluminescent waters and the Indian River Lagoon. It’s like we’re on a calendar. Once it gets a little too hot to be playing in the woods, we go play in the water. If it’s wintertime, we get on the bikes. If it’s fall, we start biking, touring and camping. If the average person spends two nights camping outside a year, I probably spend about 50. And then every New Year’s we paddle down rivers for three days. We love it.

For more information about bikepacking routes and events, visit SingleTrackSamurai.com, Instagram or Facebook.

“Wild Floridians” is a monthly original series that highlights Floridians across the state who embody the Live Wildly spirit and support conservation in unique ways. Do you know a Wild Floridian? Submit them for consideration here!